Education Was Key for the Tillinghasts. 1904 Presidential Candidate Married Into the Family

The People of Clay County History

This story is by the folks at the Clay County Archives Center.

Pioneer families – These are the men, women, and children who first lived in Clay County dating back to pre-1858, the year Clay County (AKA, the Black Creek District) was initially carved out of Duval County. To this day, the descendants of these pioneers call Clay County home. There may be no better time than the present, due to population growth and construction, to learn more about these families and their early efforts to make Clay County their own. Through a series of articles and related genealogical studies, a spotlight will focus on them and their accomplishments through the centuries and decades.

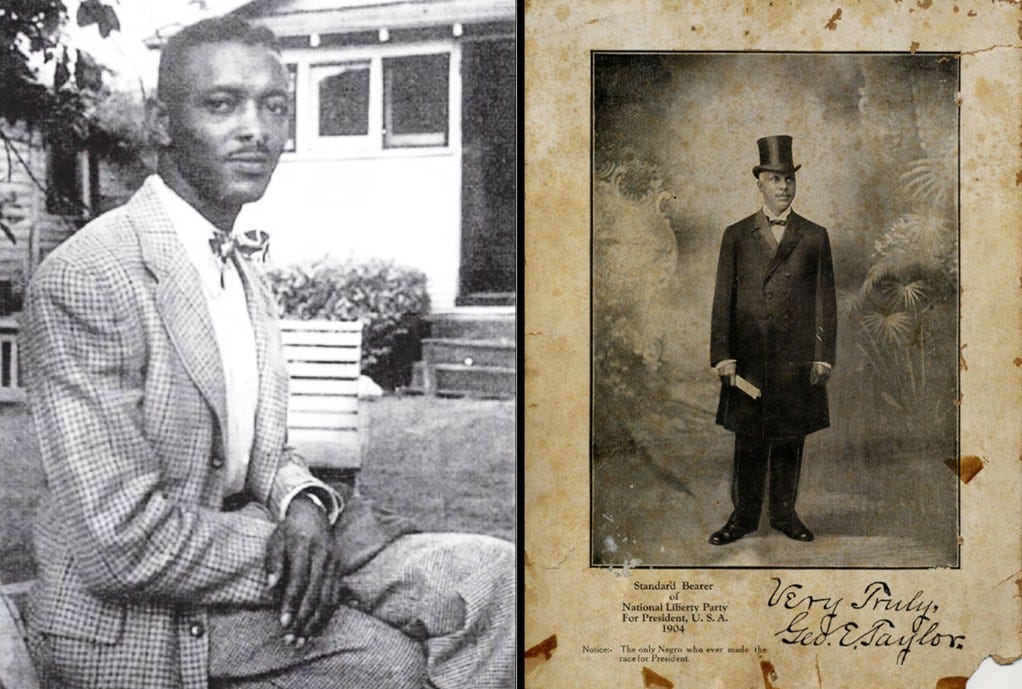

A unique figure in American history with ties to Clay County was George Edwin Taylor. Taylor was many things in his lifetime: The son of a slave, a newspaper owner and editor, a community activist, a civil rights warrior, and a bit of a radical.

In 1904, he was the first African American to run for the office of the president of the United States. In many ways, Taylor was a quixotic figure who represented a generation of African Americans whose post-Civil War dreams of political and social equality eventually gave way to the nightmare of the Jim Crow laws.

Taylor was an alternate delegate at the Republican National Convention of 1892, and for the next twenty years or so, he was very active in politics. Eventually, he grew dissatisfied with the Republican party, who he believed took the Black vote for granted. He tried out other parties and causes, until he finally joined the National Negro Civil Liberty Party.

In 1904, thirty-six states sent representatives to the first Liberty Party convention in St. Louis, Missouri. The party platform included voter disfranchisement, Black employment opportunities in both civilian and military life, anti-lynching laws, and pensions for ex-slaves. The party focused on the Democrats' disenfranchisement of Black Americans. They had nominated William Scott as their candidate for president, but Taylor became the candidate when Scott was arrested and put in jail for an unpaid fine.

Needless to say, Taylor did not win the presidency, but he gave it a good try. Shortly thereafter, Taylor moved to Florida, and that is when the Clay County connection began. By 1910, Taylor was living in Jacksonville. Whatever drew him to Jacksonville is unknown, but he quickly established himself in the Black community on the local, state, and national level.

While he politicked, he became a bit of a snake oil salesman, as he sold potions and remedies to visiting northern tourists. Journalism was still in his blood, and he was both affiliated with the Times-Union and the editor of the Florida Sentinel, a progressive weekly. In 1920, Taylor survived an assassination attempt when a load of buckshot came through his window. Fortunately, the glass slowed down the pellets enough to spare his life.

You might think this article is just about George Taylor, but it’s not. It’s really about his wife’s family, the Tillinghasts.

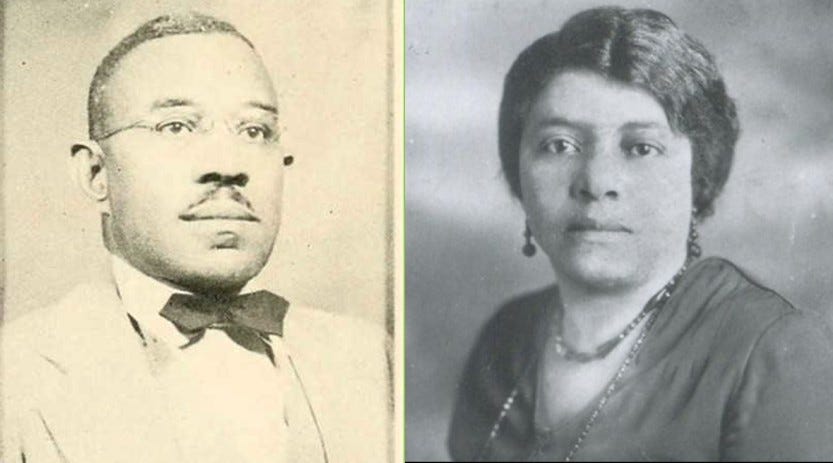

Enter onto the scene, Marion Tillinghast of Green Cove Springs. Marion was Taylor’s junior by eleven years. She and her family had been in Green Cove Springs since before 1900, originally hailing from South Carolina.

Her father, James Proctor Tillinghast, whose profession was farming, was very active in the community. He was a trustee and founding member of First African Missionary Baptist Church, located on Palmetto Street in Green Cove Springs. The church is one of the oldest in the county.

Her mother was Sarah Riley Tillinghast, and her siblings were Viola, Nellie, Clarence, Johnnie, Alice, and Sidney. Education was highly valued in the family, and Marion’s parents instilled in the children the belief that education was the key to success in life. The Tillinghasts were a powerhouse of education and service to the community, and they would later bring the same benefits to the Orlando area.

Marion and Nellie were both lifelong educators, teaching in Clay public schools, and with Nellie, also Orlando. Nellie earned her teaching certificate in 1922.

When James died in 1946, he, of course, left a debt-free estate to his children. They each inherited a portion of his home on Cypress Street. Later, in the 1960’s, the heirs sold the property. Sidney, the youngest sibling, administered his father’s estate from North Carolina, where he was an educator at Elizabeth City State Teachers College. Today, Elizabeth City State University (ECSU) is an HBCU. He was a social sciences professor.

Sidney started out as a high school principal in 1933 at Matthew William Gilbert School in Jacksonville. The school is a middle school today. He also taught at Georgia State College (Savannah State University), an HBCU, and at Bishop College in Marshall, Texas, an HBCU. Sidney himself was a 1923 graduate of Morehouse College and went on to retire from teaching at Morehouse College.

Viola was a graduate of the Orange Park Normal School, the only desegregated school in Clay County Pre-Brown vs. Board of Education. Viola Tillinghast married Rev. Hezakiah Hill, and together, they both became community activists in Orlando. In 1926, they befriended Bessie Coleman, the famous aviatrix who was the first Black woman to hold an international pilot’s license.

Coleman moved to Orlando and stayed at the church parsonage with the couple. After Bessie’s tragic plane crash, Viola escorted Bessie’s body to Chicago for burial. She took a train, and it was the first time she had ever left the state of Florida. Educator Mary McLeod Bethune was also a frequent visitor to the home.

Clarence went on to higher education, but he tragically died in 1918 of the Spanish flu before he could complete his studies. His draft number for WWI was high, and while he dodged those bullets, he could not escape the scourge of influenza. He was only 25 years old.

Alice was a homemaker most of her life. She was a seamstress who also taught the trade to students. Her daughter, Leona Mills, was a teacher at the local black high school, Jones High. Her son, John Proctor Ellis, was an active member of the NAACP and a trades teacher.

Jonnie Lee married at 17, a young age indeed. That did not stop her from becoming a teacher. She taught for 2 decades at Oakland Grammar School and LaVilla Grammar School in Jacksonville. She never had children.

Nellie married Cornelius B. Hosmer in 1914. This was the same year she was a student at the Tuskegee Institute. Hosmer was older than Nellie and a very accomplished individual. He was the Dean of Agriculture at Tuskegee. Working with the school, he published The Negro Farmer, a specialized periodical aimed at black farmers. Booker T. Washington was on the board of directors. Hosmer, a Tuskegee alum, worked closely with Washington on causes concerning the school and did quite a bit of fundraising as he traveled the Midwest. Nellie eventually divorced Hosmer. Nellie was a teacher for over 30 years and retired to her home in Green Cove Springs.

What of George Taylor, the man about whom this story began? He passed away in 1925. Marion outlived him by 36 years, passing away in 1961. She contributed decades of her life educating the young minds of Green Cove Springs. Per their death certificates, both George and Marion are buried in Mt. Olive Cemetery, Green Cove Springs. There are no headstones for them.

When it came to teaching and service, the Tillinghast Family created a dynasty of their own.