Flock Surveillance Camera Data Is Public Record, Court Says

The Clay County Sheriff’s Office Has Spent Over A Million Dollars On Flock Cameras

In the summer of 2023, the Clay County Sheriff’s Office (CCSO) quietly installed a network of cameras designed to read license plates and track the movements of every car passing through Clay County. Via a contract with Flock Safety, Inc., dozens of cameras went up overnight, covering nearly every roadway in Clay.

Flock’s cameras have been used across more than 5,000 communities in 49 states. But in recent days, the cameras have been facing increased legal scrutiny. In Washington, a court recently ruled that the data collected by the cameras is public record and therefore subject to public records requests.

This ruling, though not issued by a court in Florida, may prove to be a precedent for legal challenges in other states. Here in Clay County, the Sheriff’s Office has attempted to obscure the cameras and their capabilities by claiming that they are a) not actually cameras and b) the same as live feed cameras of traffic at intersections.

Initially, the Clay County Sheriff’s Office claimed that the Flock hardware installed was not cameras, but rather automated license plate readers. Clay News & Views was able to debunk this claim by using Flock’s own website, where they describe in detail the capabilities of the devices and refer to them as “cameras.”

Regarding the comparison to traffic cameras, Flock safety cameras differ significantly from live feed cameras used by the Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) and various law enforcement agencies. Flock cameras read your license plate, take a picture of your vehicle, and use an A.I.-powered computer program to analyze any identifiable characteristics of your vehicle. This information is stored for a year and can be used by Flock’s computer program to predict where you will be in the future. The FDOT cameras provide government agencies with a live feed of traffic. There’s no personal, identifiable information gathered, and no A.I. used to predict where you will go.

CCSO’s stance on the cameras is that they are located in public places, collecting public data. The Flock cameras have been compared to an individual standing on a street corner recording cars as they drive by. This activity is perfectly legal, as there is no expectation of privacy while in public.

But while there is no expectation of privacy in public, there is an expectation that law enforcement is limited in the methods, types and scope of data it can collect. The 4th Amendment of the Constitution guarantees every citizen the right to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures.

Given that the Flock cameras in Clay cover every major roadway and track every car that passes by, Flock cameras can be viewed as a potential violation of the 4th Amendment.

In the fall of 2023, Clay News & Views spoke with Sheriff Cook and asked if she would be willing to grant the public access to the data collected by the Flock cameras. Cook was not supportive of public access to the data, stating the data was proprietary and had the potential to be used nefariously by the public.

Claiming that the data being collected is public when it is collected conflicts with the idea that the data is private and proprietary after it has been collected. It is precisely that conflict that the court ruling in Washington addresses. The court ruled that if the data collected is public, it is therefore subject to public records requests.

Rather than comply with public requests for data collected by the Flock surveillance network, several law enforcement agencies in Washington shut down their camera networks altogether.

Regarding the risk of nefarious use of the collected data, the danger isn’t limited to bad actors outside of law enforcement. Recently, a law enforcement officer in Columbine Valley, Colorado, falsely accused a woman of stealing a package from a house, citing data gathered from Flock safety cameras in the town.

The officer confronts the woman at her home and attempts to bully her into admitting to a crime she didn’t commit. Luckily for the woman, she drives a car that records video of her trip everywhere she goes. When she advised the officer that she had video footage of everywhere she had been and could prove that she had never been at the scene of the crime, the officer became more aggressive.

Eventually, the woman was charged with a crime and had to do all of the heavy lifting to prove her innocence. And this isn’t the only example of law enforcement agents abusing the data collected by the Flock surveillance net.

In Kansas, a police chief stalked his ex-girlfriend via the flock cameras in his town.

The best way to guard against these sorts of abuses is public oversight and transparency. When asked about oversight of access to the data collected by Flock cameras in Clay County, Sheriff Cook would not commit to publicly disclosing the safeguards her agency has in place.

While law enforcement agencies appreciate the Flock devices, a growing public backlash is emerging. Communities from Massachusetts to California have rallied to oppose Flock cameras, citing concerns about privacy and potential human rights violations.

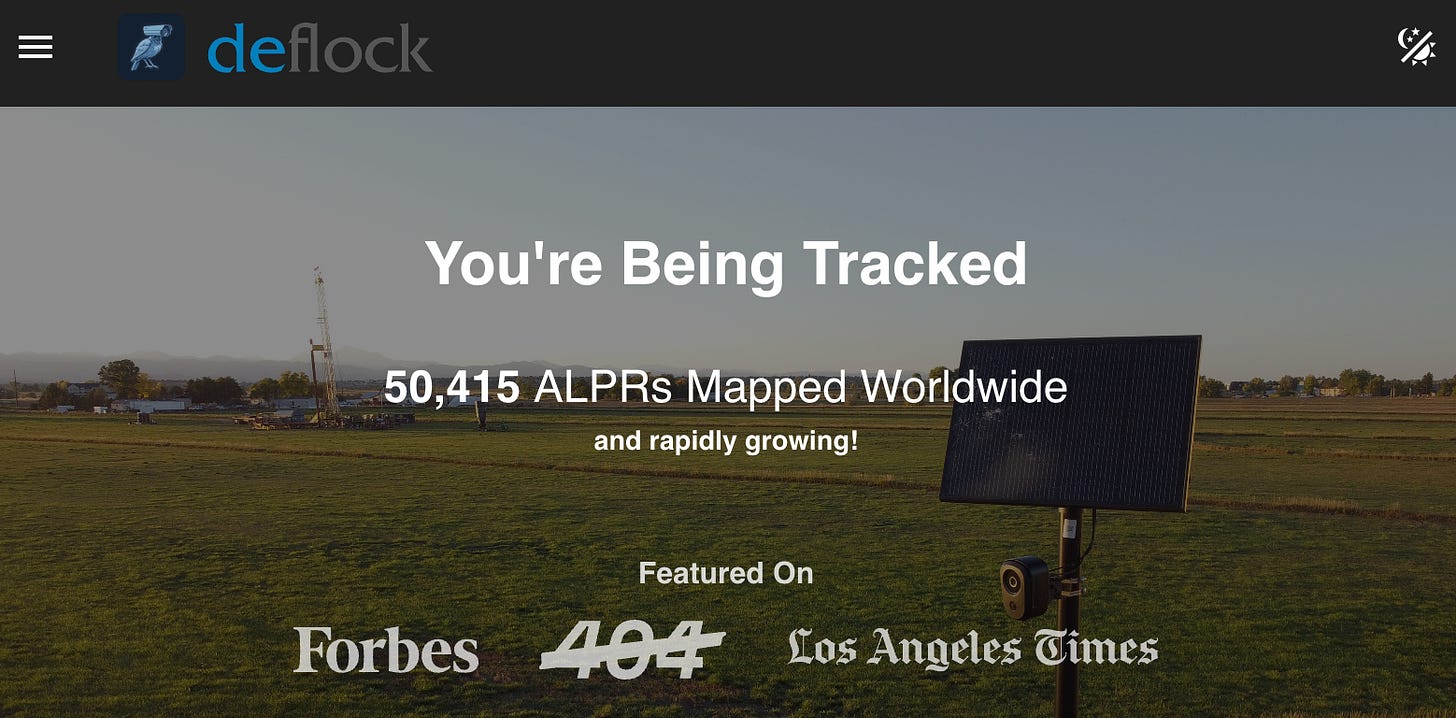

In addition to community pushback, a nationwide effort to expose and counteract the Flock surveillance network has emerged via a website known as DeFlock.me

Deflock invites people all over the country to create an account and add locations of Flock’s devices to a publicly accessible map. Android users can also download an app that will help track, map, and detail the data being pulled and monitored by Flock’s devices.

Clay Sheriff Implements $1.3 Million Surveillance Camera Network

This article has been updated to reflect information provided by Flock Safety.

I certainly would not call a license plate reader anything close to “unreasonable search and seizure” or a violation of the 4th amendment…that seems like quite the stretch.

The two examples the article cites of misuse would not have been prevented with public access to info gathered. As with any law if in the two examples the law enforcement person broke the law then arrest them. In any case I can see law enforcement’s use to be infinitely more valuable and MUCH easier to put guard rails on than the general public. Actually I can’t think of any non-nefarious use the general public would use access to the info for??

When I heard Sheriff Cook speak to it, I was left with the impression that they entered a license plate number they were specifically looking for. I could have misunderstood but I don’t think so.

The potential for abuse by a government agency is tremendous with these. They are not only license plate readers but also use facial recognition on you, as well as a similar level to identify your vehicles without a license plate.

Imagine someone, maybe during a pandemic, using this technology to see who is attending church or getting treatment for something unrelated, only to be lumped into an "infected" group. Sounds like they could bring the leper colonies to us by creating geofences and monitoring your movements anytime you step outside your house!

Oh, wait, they would never do that. We are a free people in the USA. We are allowed to accept the risk and move freely, even during crises that they have created.