Ignore the Haters on Columbus Day: The Man Had an Unequaled Influence on History

Credit a Sailor from Bradenton for Affirming His "Great Navigator" Status

We’ve come to that time of year again. Columbus Day has morphed into Columbus-bashing day, a celebration of self by indoctrinated individuals signaling virtue. Columbus-haters blame old Christopher for all manner of horrific crimes.

Leaving aside for the moment that Columbus is not guilty of the most spectactular charges and that the rest of his reported misdeeds were not considered crimes in his own time, let’s look at his unambiguous accomplishments:

Columbus was among a small handful of talented dead-reckoning navigators of the Age of Discovery;

Thanks to his rare skill, his first voyage to the Americas remains one of the most consequential, if not THE most consequential event in human history.

(“Dead reckoning” is a way of calculating one's position, especially at sea, by estimating the direction and distance traveled rather than by using landmarks, astronomical observations, or electronic navigation methods.)

“Columbus’ dead reckoning from his log was within an accuracy tolerance of 0.01 percentile,” said the late Douglas T. Peck, a scholar and ocean-crossing sailor from Bradenton, Florida. “Columbus was a genius and a visionary, whose mind could penetrate far above the mundane obstacles that shackled the minds and actions of his fellow seamen.”

Peck famously traced Columbus’s 1492 voyage on his own sailboat, effectively refuting past academics who had derided the Genoan navigator’s methods as crude.

Impact

Columbus’ first voyage changed everything. The proof is all around us, in every nation from Argentina to the Arctic. None of this was inevitable.

Yet many Columbus statues across the United States have been removed, and just maybe that’s because he really doesn’t deserve a statue. The prevailing argument is that placement on a pedestal should be reserved for those whose lives were dedicated to doing good, not for people like Columbus who merely excelled at their professions.

So, moral judgements aside, we have to respect Columbus’ skills. Some of the older boaters reading this may have grown up during pre-electronic times, having to find their way from one port to another with just a compass, a watch, a way of determining boat speed and a chart.

Remember how nerve wracking that was when you consider that 500 years before your run from, say, Miami to Bimini, Columbus had managed to cross 2,500 miles of ocean and return to port in Spain without benefit of a chart.

Columbus created the chart as he went. On arrival in the New World, his three ships explored parts of what are today the Bahamas, Turks & Caicos, Cuba, Haiti and the Dominican Republic—challenging waters even with today’s vessels and technology—before returning home by a different route. On his second voyage, he accurately returned to some of the same places, having recorded sailing directions good enough that successive captains could also come and go.

Some of the most profound insights into Columbus’ navigation skills have come not from the hundreds of academics who have studied the events of 1492-1504 but from Douglas T. Peck, who provided a much needed reality check to the historical debate.

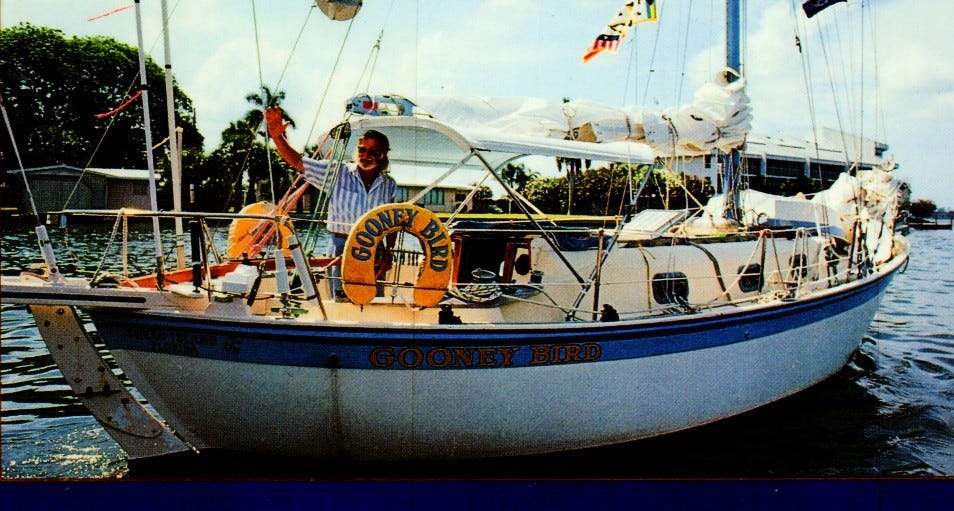

Peck was a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force who flew fighter missions during World War II over North Africa and Italy. He was a keen sailor who replicated Columbus voyage and that of Ponce de Leon in a 33-foot sailboat named Gooney Bird (a reference to a World War II aircraft, the C47).

Peck's Contribution

Peck made four trans-Atlantic crossings going from from The Bahamas to Spain. In 2011, the British Royal Institute of Navigation published his results, "The Empirical Reconstruction of Columbus' Navigational Log and Track of his 1492-1493 Discovery Voyage."

Paolo Emilio Taviani was an Italian political leader and Columbus historian. When Peck wrote his book “Cristoforo Colombo, God’s Navigator,” Taviani wrote the foreword in which he compared Peck to the great sailor-historian Samuel Eliot Morison.

This book following the research by Morison and myself, is the first valid and scientifically sound historical study of both the navigational expertise of Columbus, and the track of his voyage from Gomera (in Spain) to his landfall, accomplished by an experienced seaman and navigator.

Peck is the first to have accomplished a scientifically controlled research voyage, duplicating the track across the Atlantic by following the navigational data in Columbus’ log…This book should be a required addition in European and American libraries if they are to adequately and factually cover the history of the Columbian era.

Peck’s book contained numerous insights about Columbus and his times, including:

Genoan captains such as Columbus were considered the best in the world. Many discoveries attributed to King Henry “the Navigator” of Portugal were actually achieved by hired Genoese captains. England, too, hired its own Genoan who was the first to map the Atlantic coast of North America, including places in my native New England and maritime Canada. We know him as John Cabot, but he was born Giovanni Caboto of Genoa.

Columbus tried his hand at celestial navigation, which was in its early stages of development. He was lousy at it.

Like any educated person of his time Columbus knew the world to be round. However, he believed it to be much smaller than it is. That’s why when he reached the Bahamas, he was certain he had found “The Indies,” islands at the fringe of East Asia.

Columbus was a devout Roman Catholic—a fact that helped sell his Indies expedition to both the Spanish monarchy and its allies in the church. (Let’s just say his intentions were good.)

“Columbus believed that he was divinely ordained to bring Christianity to the New World and his motives and goals were of the highest order,” Peck wrote. “The fact that these goals were perverted by Europeans who followed his discovery can hardly be blamed on this seaman and navigator who found the route.”

Context

At the time of Columbus first voyage, Spain had been engaged in a 781-year war against Moslem invaders. In fact, the final battle culminated in the surrender of the Granada region, also in 1492. With this background of religious warfare, a battle-hardened, bloody-minded (and now unemployed) military class would treat the New World as a new campaign for riches against yet another “heretic” population.

Yes, the Catholic Church endorsed a war of conquest for the Americas with the goal of converting “Indian” populations to Catholicism, knowing full well that atrocities would ensue. The notion of “war crimes” did not exist as we know it today. Later, when Spain (and Portugal) controlled South and Central America and Mexico, the church advocated for native rights, but that impulse did not assert itself much, if at all, during Columbus’ own lifetime.

Columbus’ reward for providing Spain with access to new riches was governorship of the new colony, but he was a bad choice. His Spanish subordinates tended to despise him, the outsider in charge. The fact that the monarchy—particularly Queen Isabela—supported him was immensely important, but otherwise he had no organic constituency to politic on his behalf, unlike his often well-connected competitors and backstabbing subordinates. Think “Game of Thrones.”

Some of the charges in the anti-Columbus meme at the beginning of the story are based on possibly true events over which Columbus had little control and likely disapproved of. At one point, a Spanish nobleman who despised Columbus (and wanted his job) had him arrested and indeed took over the governorship. Columbus was sent back to Spain in chains, but Isabella saw that he was freed and provided ships for his fourth and final voyage.

Sure, he was willing to kidnap natives when it suited his mission. He meted out death sentences. But all these actions were sanctioned by the Roman Catholic Church, which was the moral authority in most of Europe at the time. Non-believers were not accorded rights, and the church even debated within itself whether Indians should even be considered human.

Columbus and the Pilgrims

The charge against Columbus that is most ludicrous is genocide. It is true that European diseases killed millions of Native Americans as infections gradually spread from Mexico south to Tierra Del Fuego and north to the Arctic. But Columbus didn’t do that. What today’s idealogues call “genocide” was an inevitable accident.

Notions of germs and disease immunity did not exist then. If the Spanish could have prevented deadly pandemics, they surely would have—if only to preserve a workforce they intended to exploit.

We recently went through a pandemic ourselves. How often did a symptomless person infected with Covid-19 transmit the disease to, say, a co-worker or family member that later died? Under the logic that condems Columbus for genocide, we would have charged these individuals with homicide, which is of course ridiculous.

The English came late to the Americas, settling Virginia in 1607 and Massachusetts in 1620. By the time the Pilgrims settled Plimouth the European diseases had spread to New England, killing an estimated nine out of 10 natives.

These “Separatists,” as the Pilgrims were then known, found empty native settlements strewn with unburied skeletons. They looted these places, taking stores of corn found there. The native Squanto, who helped the Separatists survive their first winter, was the last member of a clan that had been wiped out by plague.

I doubt that the obnoxious and incompetent collection of religious zealots who arrived on the Mayflower would ever have survived, had they come when local tribes were at the their pre-Columbian population levels. The English would have been the ones massacred, rather than commiting them.

So, you might say diseases introduced by Spanish conquerors helped make English-speaking North America possible.

Another point I wish someone else would make is that the Indians (Native Americans, Indigenous Peoples, First Nation peoples) were not one people. Scholars estimate more than a thousand languages were spoken, each representing a different culture. Columbus-haters tend to characterize all native people as innocent victims of rapacious European colonizers, an update on the “noble savage” trope popularized in the late 19th and 20th centuries.

History shows that many, if not most native tribes could be as nasty to one another as any European colonizers. They lived in a state of constant tribal warfare.

We compartmentalize what we are taught. On the one hand, we know the Aztecs ripped the hearts out of living POWs and cruelly enslaved neighboring tribes. On the other, we consider them victims of the Conquistadors who turned the tables on them.

This should not be construed as an argument that Native Americans deserved their fate. Only to make the point that past events cannot be reduced to memes. History is complicated. Context matters. And we should hesitate to condemn people who lived according to standards of their own times.

We may wish Christoper Columbus had held advanced notions of human rights and tolerance, but he did not. He was a man of the 15th century—albeit possibly a genius—doing the best he could with the skills he had mastered.

By which he triggered a tsunami of unforeseeable consequences, good and bad. That's how history works.