Sludge Is Tainting the St. Johns River, With No Solution in Sight

Dumped Farm Fertilizer Causing Toxic Algae Blooms

The author is a native Floridian. In 30 years at the Tampa Bay Times, he won numerous state and national awards for his environmental reporting. He is the author of six books. In 2020 the Florida Heritage Book Festival named him a Florida Literary Legend. Craig is co-host of the "Welcome to Florida" podcast. He lives in St. Petersburg with his wife and children. He wrote this commentary for the Florida Phoenix, which published it on July 24, 2025. It is reprinted here with permission.

By CRAIG PITTMAN

What is it about Florida’s rivers that makes us humans want to spoil them?

The Kissimmee River worked perfectly for centuries, feeding a flow of fresh water into Lake Okeechobee. Then the Army took out all the bends to stop flooding. When the Corps of Engineers realized it had created a dirty ditch that funneled pollution right into Lake Okeechobee, it spent millions of dollars putting them all back.

The Apalachicola River worked just fine, creating exactly the right conditions for spawning delicious oysters in the bay. Then people ruined the flow, which ruined the mix, and now we’ve spent years trying to bring the oysters back.

And of course, the Ocklawaha River was a wild and scenic waterway until the state built a dam that blocked the river and flooded 800 acres of the Ocala National Forest. People keep trying to tear down the dam, but Gov. Ron DeSantis has vetoed the funding for that not once but twice. (And don’t get me started on what he’s doing to the River of Grass right now.)

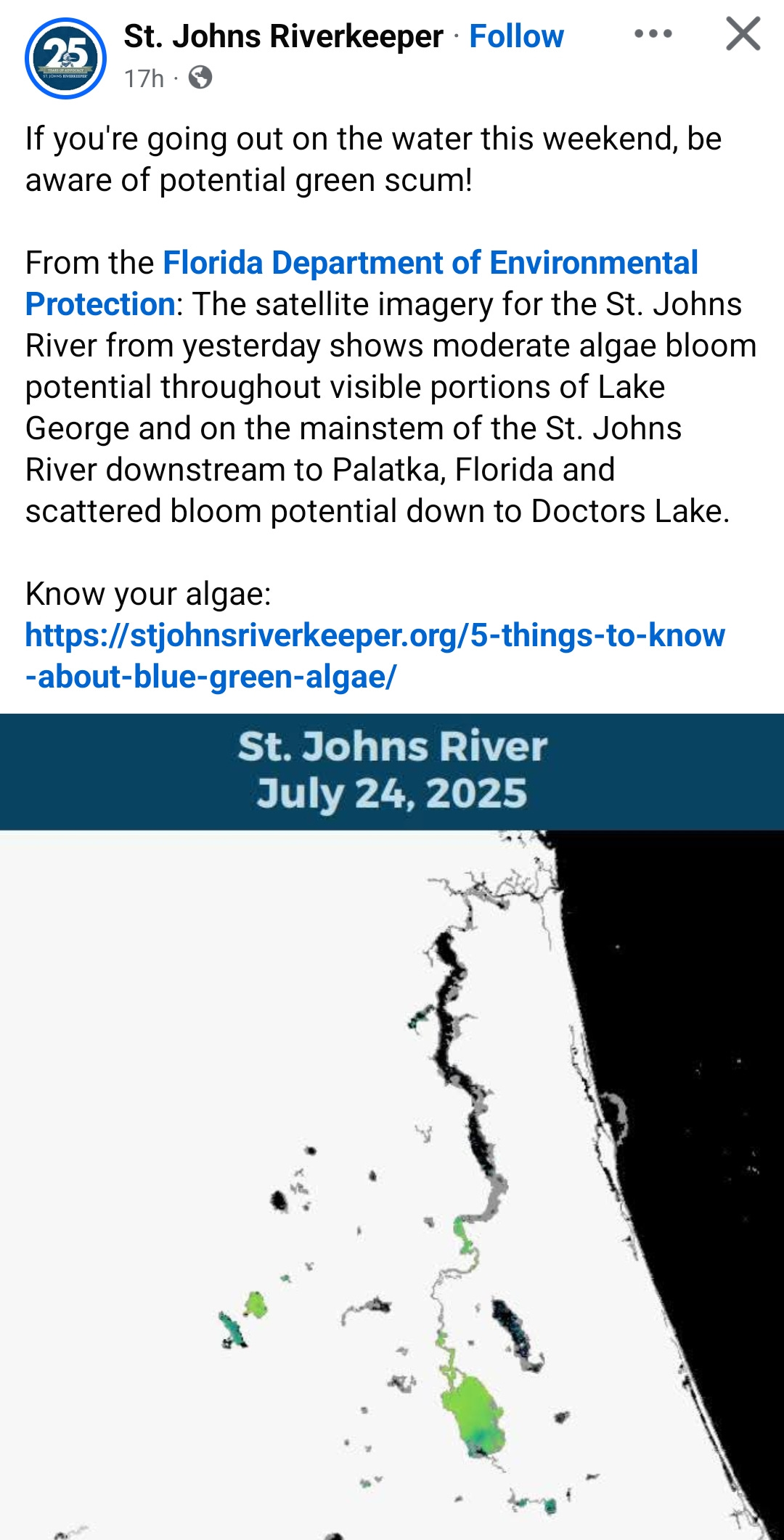

Last week, I saw a story that detailed how we’ve been messing up another Florida river, this time the fabulous St. Johns.

“Report: Miami-area sewage sludge raising cost of St. Johns River cleanup over $1 billion,” said the headline in the Florida Times-Union.

In case you’re not familiar with Florida geography, Miami is nowhere near the St. Johns River. So how is its sludge winding up there?

The paper explains that a change in state rules “triggered increased sludge-dumping in the St. Johns upper basin, around Brevard and Indian River counties.”

The St. Johns is the rare river that flows northward. That means dumping pollution in its southern headwaters leads to that nasty stuff being carried north into the river’s more populated reaches, creating the right conditions for toxic algae blooms.

The fact that the taxpayers who live along the St. Johns have been paying lots of money to clean up the river, only to see pollution from elsewhere in the state mess it up again, is particularly frustrating, said Lisa Rinaman of the nonprofit St. Johns Riverkeeper.

“We’re seeing evidence of significant pollution being transferred here from South Florida,” she told me.

What’s particularly maddening, she said, is that nobody wants to claim responsibility for fixing the problem.

Noblest Stream

The St. Johns is the longest river in Florida. It flows 310 miles from its headwaters at Blue Cypress Lake in Indian River County to where it runs into the Atlantic Ocean east of Jacksonville.

In 1843, the poet and editor William Cullen Bryant visited Florida and declared the St. Johns to be one of “the noblest streams in the country.” It’s also one of the laziest, because its elevation drops a mere one inch per mile over the course of its sluggish flow.

But its watershed is huge, covering nearly 9,000 square miles. The population of the watershed is more than 5 million people, from anglers in Palatka to shipbuilders in Jax.

The river has become the primary source of drinking water for communities in Brevard and other east central Florida counties. A 2015 University of Florida study found that it provides billions of dollars in economic impact and ecosystem services.

So even if you’re no tree hugger, you can see why a clean St. Johns is a goal worth working toward.

Like a lot of rivers in Florida, though, the St. Johns has suffered from problems of too much polluted runoff, too many water withdrawals to accommodate a growing population and the loss of wetlands wiped out by rampant development.

State and local officials were working on dealing with all those problems and had made progress.

But then the trucks began showing up from South Florida.

Sludge Is Good

While researching this column, I watched a recent meeting of the St. Johns River Water Management District, where staff members talking about biosolids abbreviated the term as “BS.” That turns out to be pretty apt.

I first learned about biosolids (and the BS around it) from a book called “Toxic Sludge Is Good for You!” by John Stauber and Sheldon Rampton, which one reviewer called “a chilling analysis of the PR business.”

That book’s title comes from a campaign to convince people that it’s OK to dump sludge produced by sewer plants and septic tanks near their homes. The PR folks advised their clients that the way to convince the public that it was OK was to change the name to “biosolids.” It sounded less frightening, less … oh, what’s the word? Oh yeah, “toxic.”

It worked — until the smell got out. Shakespeare told us that a rose by any other name would smell as sweet. Turns out that’s also true for (pee-yoo!) “biosolids.”

No matter what you call it, the sewage sludge that’s classified as “Class B” remains pretty toxic, containing lots of phosphorus and nitrogen. Those pollutants stimulate the growth of algae blooms that kill fish and other marine life. The sludge also carries heavy metals. What’s worse is that it also contains PFAS, also known as “forever chemicals.” As the Guardian explained in a recent story, “The chemicals are linked to a range of serious health problems such as cancer, liver disease, kidney issues, high cholesterol, birth defects and decreased immunity.”

Yet lots of Florida sewer plants spew this dangerous stuff out and then act as if it’s as safe as raindrops and sell it to farmers to use as fertilizer.

That became a serious problem when the haulers were dumping the sludge on land around Lake Okeechobee, because then the pollutants wound up in the Everglades.

Thus, in 2007, the Legislature passed a law that basically banned farms near Lake Okeechobee, the Kissimmee River, and the Everglades from accepting the nearly 100,000 tons of South Florida’s sewage sludge being trucked in there.

But they didn’t ban it everywhere.

As a result, the trucks simply headed north and started dumping their toxic loads at farms in the St. Johns watershed. As the state’s population boomed, they had more and more sludge to spread all over the farms there.

Suddenly the St. Johns started having serious problems with excessive phosphorus and nitrogen. And in the 17 years since the change in the law, it’s been a growing problem. By 2019, Florida Today was calling Central Florida “sludge central.”

“So the South Florida affluent have been sending their effluent up to us,” quipped water district board member Doug Burnett, a retired Florida National Guard general.

Not Enough

The water management district meeting that I watched featured a loooooong discussion of the biosolids problem.

There was supposed to be a staff report on the latest scientific findings about biosolids (spoiler alert: they’re bad but still being spread). This was the result of a study requested by the state’s environmental regulation agency.

But the staffer delivering the scientific report kept being interrupted by water district board members fuming about all the pollution being trucked in from elsewhere.

“You know, if it’s not good for the goose in South Florida, is it good for the gander in the St. Johns?” asked board member and boat manufacturer Chris Peterson. It was clear he thought the answer was no.

“As a society, we still haven’t figured out what to do when we flush the toilet,” complained board member Doug Bournique, a citrus grower.

And board chair Rob Bradley, a former legislator married to a current legislator, pointed out, “They didn’t do a study in South Florida — they just banned it.”

During the discussion, Bradley made an interesting confession to his fellow board members: “I was in the Legislature when we passed this (ban) and it wasn’t enough.”

Bradley didn’t say anything about lobbying his wife, Sen. Jennifer Bradley, to take up the cause of extending the ban to the St. Johns watershed. He may want to consider that, since his water district board held off making any decisions.

There was some discussion about people who did do something to stop the toxic pollution fouling the St. Johns. For instance, Indian River County officials, already working to clean up their lagoon, refused to allow the dumping of biosolids, district officials said.

And the state’s largest private landowner, Deseret Ranch—aka the Mormons—recently refused to allow biosolids to be dumped anywhere on its thousands of acres.

Yet the state Department of Environmental Protection, our environmental regulator, like the Legislature, continues to drag its feet about banning its use statewide.

Where To Put It

The water district folks also talked about how the DEP was trying to set new standards for the land application of Class B biosolids so they wouldn’t be quite so bad.

To me, that’s like saying, “Let’s not BAN lighting sticks of dynamite inside an orphanage. Let’s just make the dynamite blast a trifle less explosive.”

But according to Rinaman, one of the state’s largest sludge haulers has been slow to comply with what the DEP wants.

The company in question, H&H Liquid Sludge Disposal, has been around for four decades. It boasts on its website of hauling sludge “from wastewater treatment plants to farms and ranches throughout Florida.”

From its plant in Clewiston, it “has land applied biosolids for more than 30 years, strictly adhering to DEP and local regulations to ensure the safety of the community, land and livestock.”

It also notes that the dumping of Class B biosolids is “heavily regulated due to its pathogens and metal composition.” So the company knows what they’re putting on the land.

But H&H wasn’t happy about the changes DEP was proposing to the use of Class B biosolids. The company has requested they be allowed a five-year delay in complying with those new rules.

Instead of saying no, the DEP asked for more information, which is another way of delaying doing anything.

I tried contacting H&H but got no response. To me, though, the lack of swift action is symptomatic of all the other delays that are actively harming the St. Johns.

The water district folks were adamant that the solution is not to redirect the sludge to somewhere else, the way the Legislature did back in 2007. But I think they’re wrong. As Iron Man says when he grabs hold of a nuke at the climax of The Avengers, “I know just where to put it.”

I would propose that all five water districts announce that they are imposing new regulations that say the only place where haulers can legally dump their toxic sludge is in Tallahassee—specifically, at the entrance to the Florida Senate and Florida House.

Or maybe at the governor’s mansion.

I mean, it’s a problem they caused, so let them deal with it.