The County's Whopper of a Secret: Emergency (Mis)Management:

We Have Been Lucky Ducks So Far

Updated at 5 p.m. to add Susan Armstrong’s byline, inadvertently omitted in the initial version. Updated at 7:30 p.m. to fix Timothy Devin’s name.

Large or small, all governments employ people who keep secrets from the people who pay them not to keep secrets. There’s proof aplenty that Clay County has buried more secrets than we have septic tanks. Except the secrets, once unearthed, often smelled worse.

I was surprised some 30-odd years ago when in search of secrets in Clay County through public records, the keepers had them locked up tighter than Ft. Knox. When I finally got records, they had been stripped of information or were so heavily redacted that, save for a stray “a” or “and,” they had more black-outs than the Green Cove Springs power grid.

But thanks to a few honest elected officials and mostly whistleblowers with moral compasses, things have gotten a little better…sort of.

Clay News & Views has learned that the county has been hiding a whopper of a secret. As residents load up on drinking water, toilet paper and cans of chili in preparation for hurricane season, former and current staffers say local government has been ill-prepared for any catastrophic weather event for years.

CN&V obtained public records, interviewed personnel at a state emergency agency and talked with folks who have been in the thick of things in Clay’s EM department. All confirmed that the county’s Emergency Management are not the masters of disasters as much as consultants of chaos.

EM is a tiny department with a huge job. There are usually four employees that manage and direct all emergency personnel in the Clay County Fire and Rescue Department, the Clay County Sheriff’s Office and all volunteer agencies during a disaster.

John Ward, the 51-year-old former director of emergency management, seems to be swirling in the center of the secrets. He was hired in 1997 as a firefighter/emergency medical technician. Ward moved up through the ranks of the fire department with plenty of attaboys to his credit. In Dec. 2011, he was promoted to deputy emergency management director and in 2016 to director. He briefly left the agency in 2019 and then came back to resume his former position in 2020.

Local publications and the TV media reported that Ward “retired” in May 2023, just days into hurricane season. But his personnel file showed Ward was put on leave with “allegations of misconduct” pending a final decision. He then chose to retire.

Michael Ladd had been hired as the deputy director of emergency management in May 2021. Prior to that, he was an Army veteran, then the director of military support in the Florida National Guard. When Ward left, Ladd was named interim director. In September 2023, at the recommendation of County Manager Howard Wannamaker, Ladd became the permanent director. Not so permanent, as it turned out.

Six months after he became the director, Ladd left to “spend more time with his family.” But he also left behind a blistering resignation letter that painted a bleak picture of EM.

In the letter, Ladd referenced Ward’s “special retirement” and insinuated Ward had left behind a mess long in the making.

Ladd wrote that EM was “under-resourced.” He said the Emergency Operations center was “tens of thousands of square-feet short of recommended space for our population” and that the 20-plus required emergency plans were “out of date/inaccurate or otherwise in need of rewrite/update.”

He also wrote that employees who were already working over 50 hours per week had been assigned “additional duties.” He noted the county’s Emergency Management Accreditation Program (EMAP) had never been certified and the certification was “realistically at least five years away.”

According to CN&V research, an EMAP is not mandatory, even though it assesses emergency management departments to determine if they are “well-prepared, accountable, and transparent” in disaster planning. Florida history suggests that uncertified EM departments may perform badly during major disasters like hurricanes.

Tim Devin, who was hired in November of 2023 as the chief of plans in EM, was named director in April 2024 after Ladd left. He was a volunteer fireman in Clay County in 1985, then went to work for Jacksonville Fire and Rescue Department , where he was ultimately captain of the EMS training. After he retired from Jacksonville, he created a management consulting firm for private health care facilities.

(Devin’s brother and two sons also work in Clay County’s Fire and Rescue Department.)

Insiders said Devin has “floating duck syndrome.” While it looks like he is floating calmly on the surface, underneath, he is paddling like crazy to keep up and put things in order in case of a devastating event.

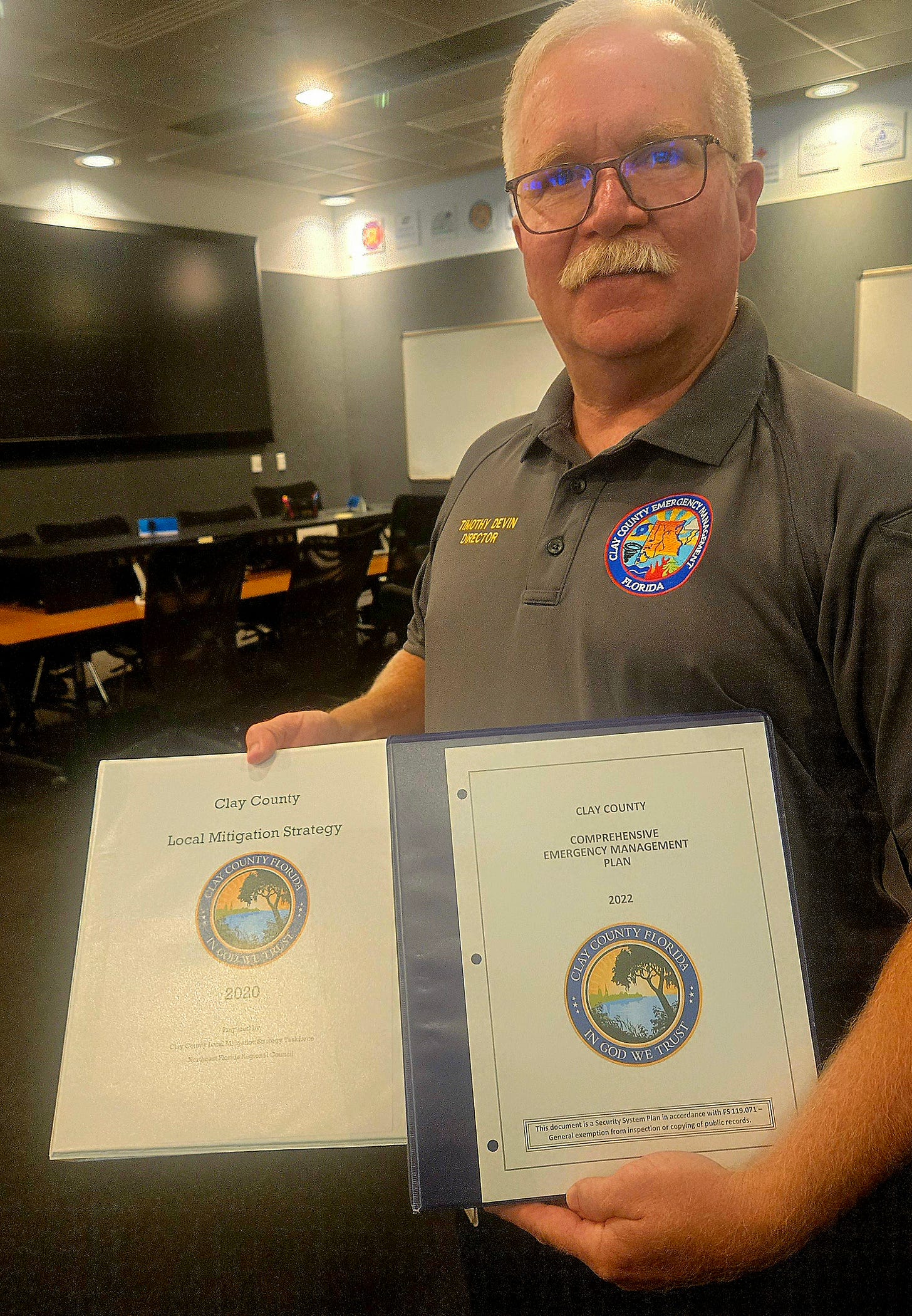

CN&V interviewed Devin. He is a soft-spoken man with a middle-aged spread, a shock of gray hair and a ready smile. We asked if EM had plans in place to respond before, during and after a catastrophic disaster like a hurricane, or if we needed to start duct-taping pool noodles together.

Knowledgeable people interviewed for this story said there were numerous different types of plans to prepare for, respond to and recover from various forseeable emergencies. Devin assured CN&V that plans were in place. We asked to see some of the emergency plans. The director showed us the cover of two, but said we were not allowed to look inside in case we might share the details with terrorists.

(Interestingly, 2020 and 2022 were the dates of the plans, which, according to Ladd, meant they were out-of-date and inaccurate.)

Employees and former employees of the county said that while the heavy lifting of emergency planning had previously been done in-house, it was now being outsourced. According to Ladd, Devin has the knowledge and experience to apply for whatever outside help or emergency funding is needed to address current shortcomings.

“Tim is the right guy for the job,” Ladd said. “Tim and his small crew are doing the best they can with the resources they have.”

According to the people interviewed for this story, Devin needs money now to begin to prepare the county for the next big one. And, these same sources said, even with immediate funding, those preparations may not be done in this hurricane cycle.

The county has not always been good stewards of our tax dollars. Officials have allowed developers to forgo paying their fair share for infrastructure and to skip out on the mobility fees that are required for all new developments. It seems there is an “oopsy” fund where the county gives Orange Park and Green Cove Springs money when they overspend on things they can’t afford.

A well-connected lobbying firm get fat checks regularly, even though we have state representatives and state senators who live within spittin’ distance to most of us and whose job it is to lobby for Clay County.

Although Clay typically has one county manager, County Manager Howard Wannamaker has appointed three deputy county managers with another in his sights. One is from finance, one is the acting fire chief and another is not acting but is the actual fire chief. Each wears two hats with extra compensation.

And the list goes on.

Meanwhile, hurricane season is here, and Clay’s citizens are like sitting ducks. Except actual ducks have a much better evacuation plan.