The Latest from the Department of Bad Ideas (Part One)

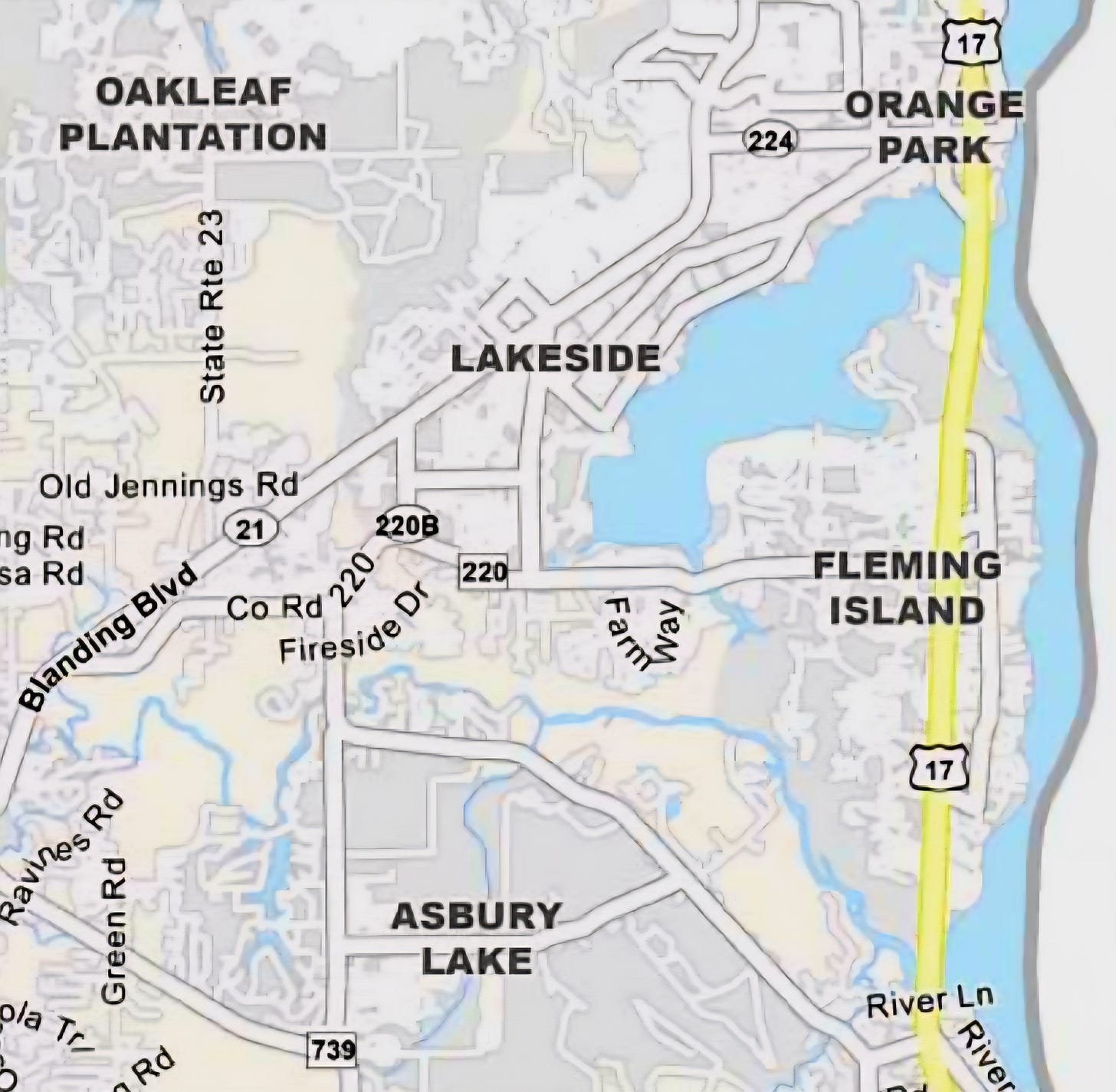

Lake Asbury, Fleming Island and Oakleaf as Its Own City?

Incorporation 101: Becoming a city is not easy, and neither is reversing the process, should folks change their minds. A 3 a.m. text from a drunken senator might be easier to undo. This is the first of two stories.

Conspiratorial whispers have been exchanged. There’s a movement brewing for Lake Asbury, Fleming Island and Oakleaf to break away and become a new city.

“Let’s incorporate.” they’re saying. What could go wrong when you turn quiet neighborhoods into budget-strapped municipalities full of strip malls, pot practitioners, Circle Ks, and enough car washes to clean every vehicle, bicycle, lawnmower and confused raccoons within a 50-mile radius?

A heck of lot!

Years ago, the incorporation of small towns were born of people dreaming of a life reminiscent of today’s Hallmark movies. But dreamers have been replaced by people desiring to supersize their bank accounts by creating new municipalities. And the supersizers are willing to pay millions in up-front costs to reap enormous paydays after incorporation.

The whispers are becoming conversations, but luckily we’ve got just enough warning to slam the door before the takeover and the damage begins.

Big Florida municipalities like Jacksonville, Miami, Tampa, and Orlando have struggled and lost the fight to balance their books even after they’ve mastered the art of squeezing taxpayers dry while flipping every patch of grass, parking lot, and pigeon perch to developers with friends in high places and blueprints for luxury condos.

To incorporate, Florida law requires expensive comprehensive feasibility studies and detailed plans as how the municipality is going to pay for employees’ salaries and pensions, buildings, garbage pickup, utilities, schools and public works—which includes the repair and constructions of all streets and roads, along with all the other things people start noticing only after they’re the ones footing the bills. Plans, of course, always show that the money will come from bonds that residents in the new municipalities have to repay and from their taxes—property taxes, sales taxes, gas taxes, and extra service taxes on everything from your phone and internet to your electricity.

After all the study and plans are approved, more money has to be expended for numerous other requirements like consultants, administrative services, and engineers for public service planning, boundaries and land surveys.

Next comes the “education and outreach” phase, which is required to inform residents within the proposed area about the proposition to incorporate. This is done by public relations professionals who create, print, and mail flyers after they slap shiny labels on incorporation—like “smart growth” or “local empowerment”—but it’s really just a clever way of saying “Get ready to pay through the nose for stuff you used to get from the county for free.”

The state requires signed petitions gathered from a percentage of residents who think they want to form a new town. To do this, canvassers are usually hired to collect signatures. Finally, the petitions for incorporation goes to the Florida Legislature for approval. Lobbyists are usually hired to influence legislators to approve the incorporation. If approved by the legislature, residents in the intended municipality get to vote. A referendum is passed by a simple majority—50 percent plus one vote.

All these state requirements are paid by the supersizers. Although unlikely, if you were able to “follow the money” spent to create the municipality through circuitous rabbit holes of dark money through Political Action Committees (PAC), shell donors, non-profits PAC, Buddy PACs, private donations and delayed disclosures, only then can you see who pays the upfront bills and, therefore, who benefits.

If the vote passes, candidates run for the local city or town council. Town council seats are typically a springboard to county, state and federal elected or appointed offices. The candidates are usually some of the same folks who sold the idea in the first place but wouldn’t know a regulatory compliance if it strutted up in high heels and introduced itself.

Some elected council members predictably believe that the city hall reflects upon themselves, so they build a fancy building, three times over budget and with a fountain that cost more than a firetruck. Elected officials hire a passel of people and companies to begin designs and build the local government buildings.

In the midst of all this, lawyers and laypeople are hired at astronomical costs to suggest positions and salaries and to write employee handbooks for all government departments which designate policies and procedures. More specialists are hired to create benefits and search for companies to provide insurance, IRAs, pensions, and workman’s compensation. All this will be paid by the residents of the new municipality.

The employees’ hiring process begins and, judging from past local government employment searches, this initially looks like a family reunion with résumés. Some folks are hired to do actual jobs, and some muckedy-mucks secure jobs for relatives that had to be painfully extricated from Roblox and Minecraft long enough to get a name tag made. Somewhere in the tangled mess of creating a municipality, more lawyers are hired on a permanent basis and charge more per month than some residents make in a year.

Once the incorporation train leaves the station, there’s little chance it’s going to back up. If a municipality has already taxed their residents into the poor house and still can’t pay their bills, they can start looking at surrounding areas to “annex” so developers can build more houses and condos and the city has more people to tax. Florida law allows this annexation—including in areas designated Rural Protection Areas—and allows rezoning for high-density development, often ignoring county land use maps and long-term planning.

This can destroy efforts to preserve rural areas, including those that are environmentally sensitive, and forces residents to pay a whole lot of money for something they never wanted.

If a town goes financially belly-up or residents realize they’ve been suckered into a vast behemoth of debt, they have the right to shut it down—but good luck finding the off switch. If residents want to dissolve their town, the municipality’s creditors are still legally protected. Consequently, residents have to assume all the municipalities’ obligations and debts including but not limited to loans, buildings, lawsuits, pensions and benefits for employees, and repayment of grants issued by the state or federal government for long term projects.

So, the odds of dissolving a town are right up there with winning the lottery. While being struck by lightning. Twice.

It’s rare, but counties have taken over the debts and dissolved municipalities. The town gets the same services, but the uniforms now have a county logo. To pay off the municipalities’ liabilities, taxes are levied on folks all over the county.

But there may be bad news coming for those hoping to incorporate the three new municipalities in Clay County.

The legislature is floating reforms to lower or eliminate property taxes. This means large and small municipalities will no longer be able to gouge property owners with huge property taxes to fund their government. Also, COVID federal assistance ended in 2024, so municipalities will not have these funds in their budget.

If the folks in Fleming Island, Lake Asbury and Oakleaf are not clutching their wallet like it’s the last roll of toilet paper in a pandemic—then buckle up. These aren’t just possibilities, they are the official playbook for the incorporation of a municipality and will affect the entire county.

Thanks for the heads up ... this is a NO GO for this household!

For higher taxes and more complicated run-around, you might get an extra day of garbage pickup and recycling. Don't do it.