What Was Clay County Like During America’s “First Thanksgiving”?

Spoiler Alert: There Was No Cranberry Sauce

The “first Thanksgiving” is traditionally dated to 1621 in Plymouth, Massachusetts—a harvest feast between English Pilgrims and Wampanoag people. Fast-forward (or south, really) to the same year in what we now call Clay County, Florida: This inland area along the St. Johns River, about 30 miles southwest of modern Jacksonville, was a vastly different world. It wasn’t “Clay County” yet (that came in 1858), but a lush, watery landscape inhabited primarily by Timucua-speaking Native Americans.

Clay County in 1621 was a subtropical paradise of wetlands, rivers, and forests—think dense hammocks (evergreen forests), cypress swamps, pine flatwoods, and the slow-flowing St. Johns River snaking through it all. The region sat in the heart of the St. Johns culture (an archaeological tradition dating back to ~500 BCE and persisting into the 17th century), with villages clustered near rivers, lakes, and estuaries for easy access to resources.

Shell middens (trash heaps of oyster shells and bones, some up to 25 feet high) dotted the shores, evidence of heavy shellfish harvesting. Burial and ceremonial mounds—built from sand and topped with wooden structures—rose 4–15 feet high and were used for rituals and to house chiefs. The climate was mild and humid, with year-round rain supporting abundant wildlife, but poor soil limited large-scale farming.

The land belonged to the Timucua, one of Florida’s largest indigenous groups, with an estimated 200,000 people across northeast Florida and southeast Georgia at European contact (though diseases were already slashing that number by 1621). In this area, it was the eastern Timucua subgroups, such as the Utina (along the middle St. Johns River from modern Palatka to Lake George), who called it home.

They lived in loose chiefdoms—about 35 total across Timucua territory—each with a few hundred people spread over multiple villages of 30–40 circular thatched houses (palm-frond roofs on pole frames, about 20–30 feet across). A massive council house in each village could hold up to 3,000 for meetings and ceremonies.

Society was matrilineal (inheritance through the mother) and clan-based (clans named after animals such as deer or turtles). Chiefs (caciques) led with input from councils of elders, starting days with the “White Drink”—a purifying emetic tea from yaupon holly that induced vomiting for spiritual cleansing (men only).

People were tall (men averaged over 5’4”), tattooed with symbolic designs using ash-rubbed pokes, and dressed in moss capes, deerskin, or nothing in the heat. They played intense ball games (like early soccer or lacrosse) for fun and rivalry, danced around fires, and hunted with bows.

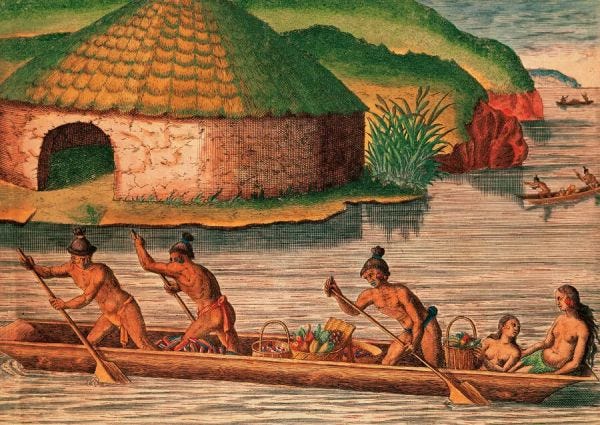

Life revolved around the water and wild bounty—no plows or wheels, just living off the land. Men fished with nets and hooks (catfish, mullet), hunted deer, alligators, and birds with arrows, and gathered shellfish. Women farmed small plots (maize, beans, squash, tobacco) cleared by slash-and-burn, plus foraged berries, nuts, acorns, and koonti roots (ground into flour for bread).

Everything was boiled in pottery (chalky St. Johns ware, sponge-spicule toughened) or roasted over barbacoa grills. Granaries stored surplus, and trade brought in exotic goods, such as copper, from the north. It was semi-nomadic in lean times, but villages were semi-permanent hubs of feasting, storytelling, and mound-building rituals where bones of the dead were bundled and reburied.

Spain had claimed Florida since Ponce de León's 1513 expedition, but real intrusion began with St. Augustine’s founding in 1565, about 40 miles northeast of Clay County. By 1621, Franciscan missions were popping up in Timucua lands to convert and “civilize” (e.g., Nombre de Dios near St. Augustine, or early ones like San Juan del Puerto in Saturiwa territory).

These were self-sufficient villages blending Timucua homes with churches, introducing pigs, chickens, wheat, and Catholicism—Timucua adapted, exporting corn to Spain while keeping ball games and White Drink ceremonies. But it wasn’t all peaceful: Early contacts brought smallpox and other diseases, halving populations by the late 1500s, plus raids and forced labor.

In Clay County’s inland spots, Spanish boots were rare—more river traders or missionaries than settlers—but the Utina were already feeling the pressure, with alliances forming and fracturing. In short, 1621 Clay County was a vibrant Timucua heartland of riverine villages, mound-top rituals, and wetland feasts—far cry from Puritan turkeys up north. Spanish influence was creeping in like morning mist, setting the stage for bigger changes.

A good picture of that vanished world. But it should be remembered that intertribal alliances and warfare were facts of life for centuries before Europeans arrived.