Yes, Mooring Fields Deter Derelict Vessels, But They Can Also Be a Huge Boon for Local Boaters

Why Green Cove Should Adopt BYOB (Bring Your Own Buoy)

We don’t need a high-buck consultant from Tallahassee to tell us that anchored boats in our small Florida town are problems waiting to happen. Confronting the derelict-vessel issue, local leaders in Green Cove Springs have begun planning for a mooring field somewhere within their jurisdiction on the St. Johns River in North Florida.

The reasons for doing so are twofold:

Self-Defense: A growing number of deteriorating vessels anchored here are waiting for the next nor’easter to sink them or set them free—in a bad way. Sadly, no one has figured out a way to restrict people who have no business owning boats that size without also penalizing those that are competent mariners, unlikely to cause problems. State law prohibits anchoring in an established mooring field.

Future Cruisers: A new beltway is being built around Jacksonville, and as part of the project, the state will replace a 45-foot bridge over the St. Johns River with a standard 65-footer before the end of the decade. The higher span will open the river to cruising sailboat traffic all the way to Sanford, 85 miles to the south. Recreational traffic on the river is expected to increase dramatically, especially in fall and spring, as snowbirds traveling on the Intracoastal Waterway explore a previously unavailable, scenic detour.

Local leaders see the mooring field as a win-win. So far, so good.

Here’s the Problem

Ever since the city of Marathon cleaned up Boot Key Harbor by establishing a well-regulated mooring field two decades ago, subsequent Florida municipal mooring fields have followed the same template, and maybe it made sense for St. Augustine to do it that way, and now Jensen Beach and soon Riviera Beach.

But, as Loose Cannon recently urged our city manager, now might be a good time to start thinking outside the “Florida box.” Let’s call the proposed alternative the “Maine model,” even though several other coastal states do the same thing. Maine just happens to have a town similar in many ways to Green Cove and good for comparison.

Back when I wore a tie to my day job, I also served as a member of the Salisbury (Massachusetts) Harbor Commission. The town of Salisbury fronted on the Merrimack River, and the commission’s job—we were all volunteers—was to advocate for best practices on the river, including management of a mooring field.

More pertinent to this discussion, however, was our dedication to ensuring that town residents—ordinary folks—were able to continue to enjoy the river in the face of commercial development.

There’s good reason to look outside of Florida for inspiration. Moorings are a new phenomenon down here, but in the Northeast they have been a part of waterfronts since the 1950s and even earlier.

Thus far in Florida, mooring fields follow the same pattern, whether they are administered by local government or a private marina. The entity gets permission from the state Department of Environmental Protection, purchases the gear (referred to as “tackle”) for the moorings, installs the moorings, and then rents them to boaters on daily, weekly, monthly or yearly basis. Boaters must show proof of insurance.

Kittery, Maine

Kittery, Maine, has 480 moorings, 240 of them in a place called Pepperell Cove on the Piscataqua River. Overlooking the cove is a quaint small-town waterfront not unlike that of Green Cove.

Unlike anywhere in Florida, however, all but about 10 of its moorings are owned by individual boaters, not the town of Kittery.

Yet, the control that Kittery has over all aspects of its mooring fields meets, and possibly exceeds that of any in Florida, because of oversight by a guy named John Brosnihan, retired Coast Guard and police officer. Brosnihan is Kittery harbormaster, a position that demands and gets respect.

With authority derived from the state of Maine and the town of Kittery, Brosnihan assigns each applicant a permit for a specific space in the mooring field. He requires applicants to provide tackle suitable for the type and size of their vessels—as determined by him—at their own expense. An applicant must pay a contractor, also approved by him, to install the mooring, and the condition of the tackle must be inspected by approved divers at specific intervals.

The boatowner must reapply for their mooring permit annually. The fee is based on the length of the boat—at the moment $8 a foot.

In almost all aspects, the Maine and Florida models are indistinguishable in quality control. So, those things being equal, why follow the Maine model on tackle ownership?

Because the Maine model would provide the most benefit to citizens of Green Cove Springs and Clay County. It maximizes public access for responsible local boaters, saves local taxpayers money and has the potential to bring more customers to local businesses.

Earlier, I mentioned that the underlying problem behind the derelict boat crisis was our inability to screen out local boatowners lacking wherewithal to properly “husband” their vessels at anchor. (That’s a New England term along the lines of “animal husbandry,” as taught by 4H.) The Maine model provides the screening device that we now lack.

Paying for their own tackle allows boaters to save money in the long run, and it saves taxpayer money up front. As boats and boating become increasingly expensive, we run the risk of squeezing out the middle-class from responsible boat ownership. The own-your-own model is a proven equalizer.

Moorings have four elements: An anchoring device—either a heavy object or a helical screw, a “rode” usually combining chain and line, a float or buoy (think big ball) and a pennant or pennants, which are short lines from the buoy that the boat attaches to. The anchor is the biggest expense.

Florida in general and the St. Johns River specifically are blessed with sand and mud-sand bottoms ideal for helical screw installations, which have an excellent track record down here. (Alas, Maine has too much subsurface ledge for widespread use of helical screws.)

Helical Moorings

Peter Morrison of the Helix Moorings systems provided pricing for moorings suitable for the waters off Green Cove rated for Category 2 hurricane winds. (The city’s initial report mentioned 60 mph, but a 110 mph standard makes more sense, given the exposed nature of the river here.)

According to Morrison, the screw assembly for boats up to 35 feet would cost $1,500 to $1,550, while screws for 35- to 50-footers would cost $1,750 to $1,800.

Though several factors determine installation costs, including a need for special equipment, one could expect the total cost for an individual helical mooring to be about $4,000.

Residents of St. Johns County must pay $2,800 a year for a mooring at the St. Augustine Municipal Marina. (Non-residents would pay nearly $7,000.)

For comparison: An own-your-own tackle policy would cost Green Cove and Clay County residents, say, $4,000 plus annual mooring fee, plus insurance.

After that initial investment, however, the equation gets better fast. By year two, mooring holders would have spent lot less than the St. Augustine customer. Assuming the Kittery rate, an owner of a 40-foot boat, for example, would pay only $320 a year, plus diver-inspection fees. Keeping a boat in Green Cove would be a bargain.

Consider the upfront costs and mandatory insurance to be a “qualifier.” The ability to pay for tackle and its installation effectively ensures that moored boats will belong to people unlikely to let them become derelict.

For the state to approve a municipal mooring field, the city has to provide certain amenities shoreside, such as bathrooms with showers, washers and dryers, Wi-Fi and maybe a temporary pass to its famous spring-fed pool. Some infrastructure items would be must-haves, including a dinghy dock and a system for removing waste from boats’ onboard sewage systems. Green Cove would need a pump-out boat.

As Harbormaster Brosnihan might inform Green Cove’s leaders, if they were to ask, the city need spend very little in local tax money for this at the outset. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a grant program for marine infrastructure that will cover 75 percent of the cost of those amenities.

In fact, the feds will cover 75 percent of the cost of the pump-out boat, 75 percent of the gasoline to operate it, and 75 percent of cost of staffing the boat—all for seven years. By the end of that time, the city’s harbor revenues will probably have become sufficient to continue to cover those costs. As we learned at the Salisbury Harbor Commission, outboard motor manufacturers are often willing to donate a motor to the cause.

Habitat Moorings

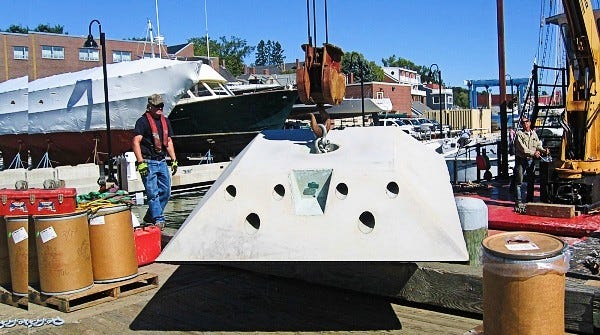

Under the Maine model, a municipality can install its own moorings as it sees fit. Green Cove could set a precedent in Florida by choosing “habitat moorings” instead of helicals for its share. Habitat moorings are specially modified concrete blocks. Holes molded into the block would provide habitat for blue crabs and juveniles of the many species that make the St. Johns River a fishing destination.

Habitat moorings—which can weigh up to 12,000 pounds—would benefit local crabbers and make fishing from the city pier or small craft more rewarding.

Just for fun, the man behind Habitat Mooring Systems, Stewart Hardison, quoted $900 each for 4,000-pound blocks, assuming an order of 20. By the time they shipped from the factory in Maine on flatbed trucks, equipped with rode and ball and positioned by barge, the price may well be around the same as a helical installation. If the city were to ask, there’s a good chance that the feds would pick up 75 percent of the tab because of the environmental benefits.

Go Big

Green Cove has an estimated .6 of a square mile off its waterfront suitable for moorings. Preliminary plans define the mooring field as a couple of rectangles within city waters with moorings neatly arrayed in ranks and files like soldiers on a parade ground. It’s as if the consultant who drew the plans wanted to keep the customers fenced in. It’s tidy, symmetrical and entirely unnecessary.

Why not just make most, if not all city waters a mooring field?

If the city were an old fashioned shopping mall, it would have two “anchors,” so to speak. There’s the historic downtown at one end with restaurants, bars and shopping. On the other, where Governors Creek meets the river, there’s a shopping plaza with groceries, more restaurants and an excellent hardware store. Both have landings for dinghies and are a 20 minute walk from one another. They are separated by an area that is mostly residential.

Why not cluster the city’s transient moorings around these two locations? Why not let local mooring applicants choose their own spots on the river, at least in the beginning? Most would probably choose to be near the dinghy landings, but maybe not everybody.

Not every Green Cove waterfront property owner has a dock; some of them might want a mooring in front of their homes so they too can own a boat, one they can keep an eye on. Even homeowners with docks might want a mooring. The entire city waterfront is open to the northeast. Unless it's on a lift, a boat is almost always safer from damage during a blow when attached to a good mooring, instead of being banged up against pilings.

Master of the Harbor

As mentioned early on, Kittery only has a handful of city-owned moorings, but it has a program that allows individually owned moorings to be available for rental to transients if the owner’s boat is out of the water or elsewhere for an extended period.

Which brings us to the issue of management. So far, under the Maine model, Green Cove Springs taxpayers would have had to pay very little. But for any of this to work, there needs to be at least one and possibly two new city positions created. There has to be a harbormaster and probably, at some point, a deputy harbormaster.

Fortunately, record-keeping has been automated. Harbor management software is available to keep track of the status of every mooring—fees paid, inspection due dates, sewage pump-out history, etc. It also allows transient boaters to reserve a mooring ball online and takes payment via credit card. Mooring-holders have access to their own section of the website, as do approved contractors to theirs.

At least a portion of the harbormaster’s time would be assigned to operating the pump-out boat, so part of his or her salary (and later a deputy’s) could be paid from federal pump-out funds. Brosnihan said his department is now largely self-funded from revenues earned by slip and mooring ball rentals, and this is a state with a boating season that is barely five months long.

45-Day Anchoring Limit

Green Cove—and Clay County for that matter—should follow the precedent recently set by Broward County, which has established 45-day limits on anchoring during any six-month period. The new rules apply to two large basins off the Intracoastal Waterway south of Lauderdale. (There is exemption for imminent or existing hazardous weather.)

BoatUS is a division of Geico insurance and has a history of lobbying against limits on anchoring in Florida, but not this time.

"We believe 45 days is a reasonable time frame for a vessel to remain in a particular area and will allow all active, responsible cruising and recreational boaters to use, anchor, rest, repair, visit, re-provision, and enjoy these bodies of water," BoatUs lobbyist David Kennedy said. Among more than 800,000 BoatUS members, nearly 180,000 call Florida home, and many are snowbird cruisers who pass through the state.

Such a measure that should be adopted as soon as possible in Green Cove and Clay County. Once a mooring field is in place, boaters who still prefer to anchor (in whatever space is left) should be required to pay a fee to use dinghy dock facilities—say, $10 a day—thus creating an incentive to rent a $35 ball for the night instead.

Not Invented Here?

No doubt, some of these ideas will meet resistance, falling as they do under the category of NIH. As I mentioned in an earlier article, consultants and lobbyists play an outsized role in Florida governance. In this political environment, the interests of ordinary citizens can be easily overlooked.

The Maine model offers Clay County folks access to boating on the river at a lower cost than being at a marina. It can benefit anyone with a vessel too big, or a pain in the butt to trailer. It would make Green Cove a destination not just for northern boaters exploring the river, but for residents from all over the county who could moor their boats here and visit on weekends.

The own-your-own model would let the mooring field grow organically rather than having to spring into existence full-size, all at once and at taxpayer expense. By the time federal grant money ran out, the own-your-own mooring field would have been built-out and likely be self-sufficient financially.

Waterfront homeowners—I was once one of them—might worry that having boats moored out front is somehow a detriment. But they shouldn’t. The process is designed to screen out the riff-raff. The boats will be in good shape. And if something offends, your harbormaster will sort out the problem. That’s part of his job. This system has worked smoothly for decades elsewhere. There’s no reason it wouldn’t work here.