Seminole Wars Were Tough Times Hereabouts

Celebrating Clay County History

By CLAY COUNTY ARCHIVES CENTER STAFF

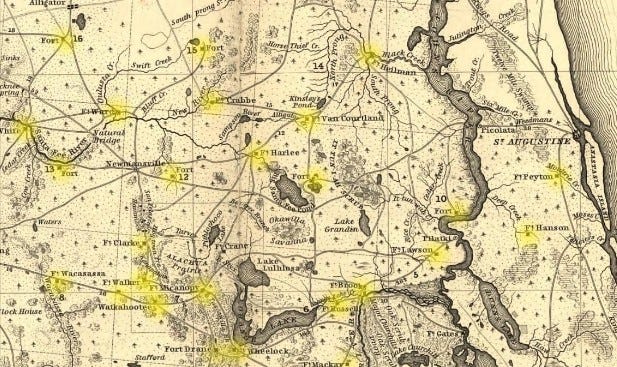

Clay County was not left unscathed during one of the cruelest wars ever fought on our nation’s soil—the Second Seminole War. As a matter of fact, Garey’s Ferry, at the forks of Black Creek, was the epicenter of supply distribution during this war.

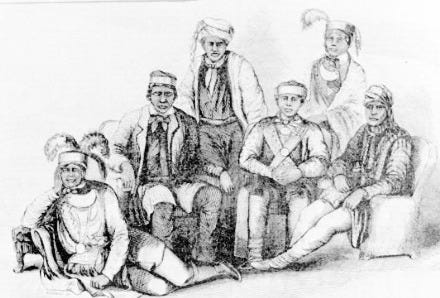

Back in 1835, Clay County wasn’t known as Clay County. The area was a portion of the territory of Florida and was considered a part of Duval County. Things were heating up in the battle to forcibly remove the Seminoles from Florida. As a result of the Treaty of Payne’s Landing (1832), the Seminoles were a hunted people. The treaty required that they leave Florida and relocate to west of the Mississippi. They did not want to go.

They felt they had been tricked and coerced into signing the treaty, so leaders like Osceola, Jumper and Micanopy, to name a few, engaged the U.S. government in a war that became the longest and costliest removal war ever fought. The Seminoles and their allies struck at both soldiers and settlers with a stealth and ferocity that caused the populace to tremble in fear and to seek refuge at local military forts.

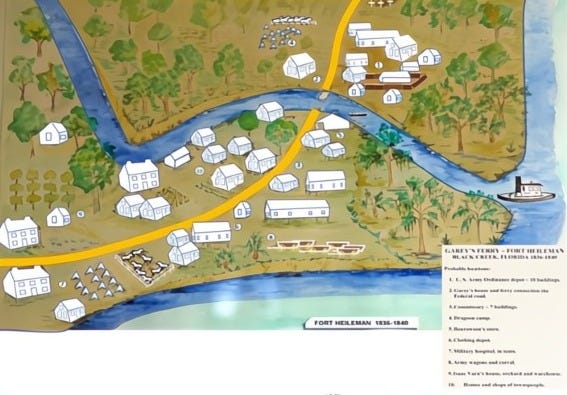

One such fort was at Garey’s Ferry. The ferry was located at the forks of Black Creek, where the Middleburg boat ramp is located today. Under the orders of General Winfield Scott, Major Julius Heileman established a fort at Garey’s Ferry. Isaac Varnes, whose land the fort was located on, later complained about the soldiers cutting his valuable timber and trampling his crops in the field. An ordinance depot was built across the creek from the fort. It’s not smart to keep ordinance in a fort, hence its removed location.

The fort served its purpose well. Refugees flooded in for protection. The fort supplied the bulk of ordinance and other supplies for the outlying forts in Northeast Florida. Because of the flood of refugees at Garey’s Ferry, sickness was rampant and medical care was scarce. Both soldiers and civilians were in dire need of assistance. In September of 1836, Garey’s Ferry reported 150 sick soldiers out of fewer than 250.

Stories like what happened to the Johns family were a major motivator to come into the fort. The Johns family, living near Black Creek, was among some of the earliest victims of the war. The family hailed from Georgia and were among the first settlers of the Black Creek District, as Clay County was called back then.

In September of 1836, warriors raided their home. It was about 11 on a Thursday morning when a raiding party came upon Mr. and Mrs. Johns. They were fired upon, and Mr. Johns was wounded in the chest. Both ran for the house. The Indians called out to them in English for them to come out and said they would not be hurt. The couple refused and instead begged for their lives. The order was given in English to charge the house.

The warriors burst in and shot Mr. Johns in the head. One man grabbed Mrs. Johns, dragged her out the door, and told her to “go”. At that very moment, she saw a warrior raise his rifle at her, and she threw her arms up. He shot. The bullet went thought her arm and passed through her neck. She fell to the ground and “played dead” as she was scalped alive.

The house was ransacked and burned to the ground. Bleeding profusely from her head wound and bullet injuries, Mrs. Johns crawled and stumbled into the swamp and laid there until late in the evening when three men (her father-in-law Mr. Luke Johns, Mr. Lowder, and Mr. McKinney) found her. She was taken to a neighbor’s home, that of the Sparkman family.

The Sparkmans, who were both good friends and in-laws to the Johns family, took her in and helped her recover. Major Pierce, posted at Garey’s Ferry, received the news and sent three companies of soldiers to look for those responsible. They were never found, having slipped away. Mrs. Johns survived her wounds and later remarried to a man named Mathas. Tragedy seemed to follow her, though, as her new husband was stabbed to death in Savannah. Mrs. Johns died in 1874.

Both Luke and Lavinia Johns, as well as the Sparkman family, were listed on the 1837 refugee rolls at Garey’s Ferry. Other Clay County pioneer families seeking refuge at the fort were Bardin, Blitch, Hagan, Padgett, Moody, Thomas, Osteen, Prevatt, Silcox, Varnes, Wiggins and Wanton. Garey’s Ferry was renamed Ft. Heileman after the death of Julius Heileman and would be used until 1841.

By 1842, the war was declared a draw. Neither side won. The government lost at least 1,500 soldiers, and the number of Seminoles lost is unknown. Some were forcibly removed to what is now the state of Oklahoma.

The Third Seminole War (1857-1858) was the last war fought by the Seminole people. It was led by Billy Bowlegs, and at its end, fewer than 500 Seminole were left. They lived in the Everglades, where they survived quietly. Their descendants are today’s Seminole Nation.