Tan McDower and Family of Orange Park Worked in Turpentine, Then Took It Further

This Month in Clay County History

The author is supervisor of Clay County Archives, a service of Clerk of Court and Comptroller Tara S. Green.

By VISHI GARIG

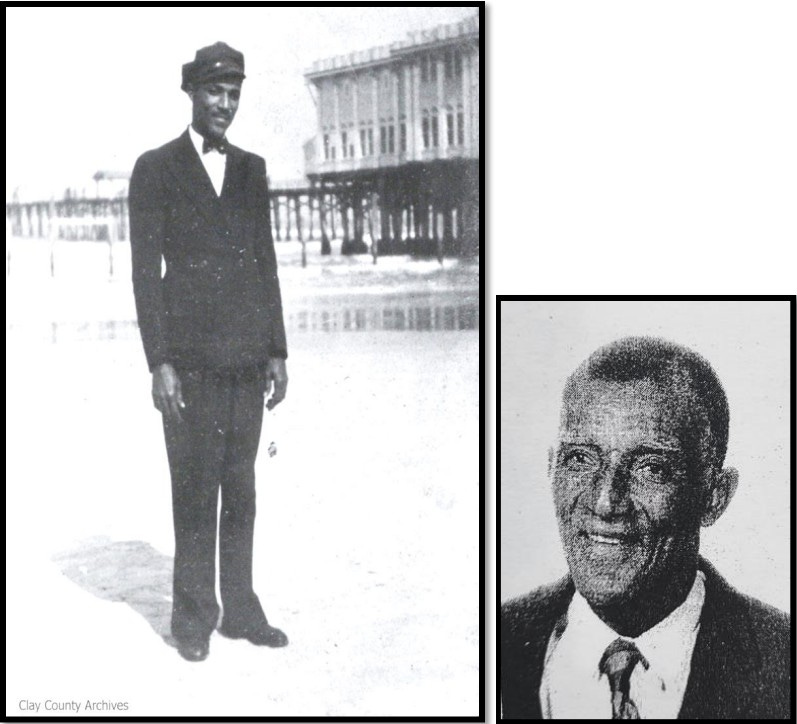

Tan McDower and his brothers Beatrice (yes, you read that right), Ed, and Macon, arrived in Orange Park, Florida, sometime in the late 1920s. They hailed from Monticello, Florida, but their parents, John H. McDower and Elizabeth Macon McDower, were both from Mississippi.

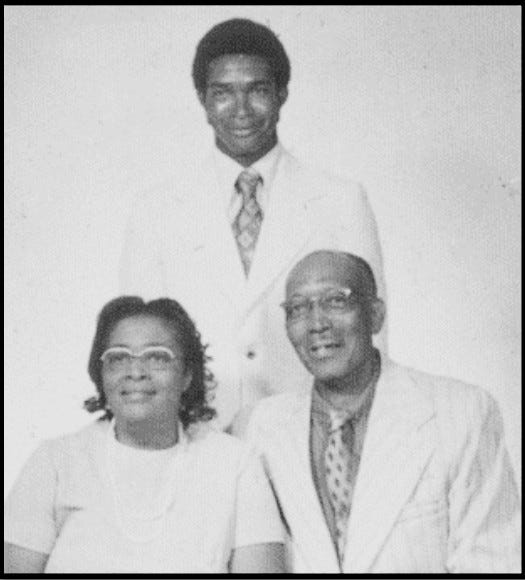

Tan, whose full name was Artanzar, found true love when he met Annie Elizabeth Jones. They were married in Orange Park on March 4, 1930. Annie was sixteen years old then, and Tan was not much older at eighteen. But their young marriage began a lifelong road of hard work and dedication to each other.

There would be potholes in the road along the way, but at the end of the journey, they were together and earned a place in Clay County history. Like Tan and Annie, Tan’s brothers were hard workers. Ed and Tan created small businesses together and invested in real estate. But before that, all four brothers became involved in turpentine.

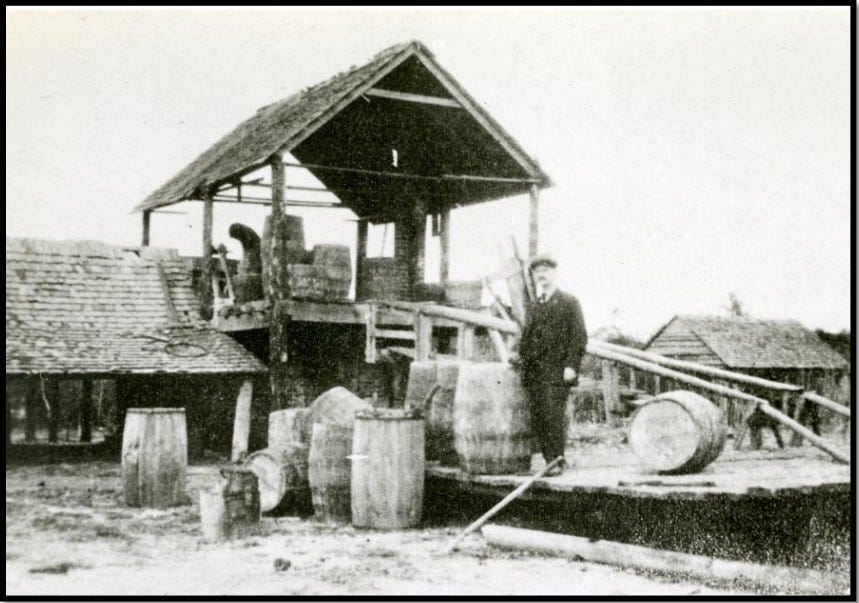

In the 1930s and ‘40s, Ed and Tan worked at the Olan S. Howard Turpentine Camp just north of Middleburg. Later, Tan and Annie moved to the Howard Worker Settlement in Orange Park. Beatrice and Macon worked at Howard’s for a bit, too.

The McDower Family was crucial to the development of the black community in Orange Park. Both Ed and Tan knew that working turpentine for someone else was a dead-end job. So, they pooled their scarce resources and started up their own pulpwood and turpentine business. They started out by leasing land.

Tan had an uncanny talent for being able to estimate to the barrel how much sap a tree would produce over its lifetime. To keep a tree alive, the cutting of the cat faces into the tree had to be completed in a particular manner, and the brothers made sure everything was done correctly. The brothers’ father, John McDower, had worked in a shingle factory and was able to pass knowledge about timber and turpentine along to his sons.

The business grew, and they were able to buy trucks and provide good, steady work for local young black men. The 1950s and ’60s were a prosperous time for the McDowers, as the family, particularly Ed and his wife, Bertha, began to dabble in real estate. In 1955, Ed and Bertha invested in eleven parcels of land close to Tan’s property, and Beatrice and Macon also purchased land in Orange Park.

Beatrice and his wife, Eula Mae, who lived next door to Ed, were running a plant nursery. In 1950, Tan and Annie purchased six acres along Railroad Avenue. Every spare dime earned was used to pay off that loan, since land ownership was a sure path to the American dream. Tan and Annie’s land was so precious to them that when they had a falling out that resulted in Tan relocating to Long Island, New York, he sent money home to pay the taxes.

Annie wasn’t having it, so she divorced him in 1956. The breakup was one of those axle-breaking potholes in the road of life. Fortunately, the separation didn’t last long, as they remarried in 1958 and were together ’til death did they part.

Tan and Annie never had children, but they unofficially “adopted” Annie Lee Keys. In the 1980s and 1990s, Macon and his wife, Lillie May Wicks, were still involved in real estate. Macon won a quiet title lawsuit1 regarding a parcel that was in dispute.

In 1986, the Town of Orange Park resurveyed its town limits. Macon had created an eight-house subdivision about 50 years before that. The new town limits placed his smaller wood frame house in the Town of Orange Park and split his subdivision in half. Willie Jones, a neighbor, lived in a home whose living room ended up being in the Town of Orange Park, while his kitchen and bedroom were in unincorporated Clay County.

Ed and Bertha began to sell off some of their holdings in the 1980s, as did Tan and Annie. Tan and Annie sold lots to their friends and family, among them NFL players Dez and Adrian White. By the time it was all said and done (around the time of the passing of the elder McDowers) the black community defined by Railroad Avenue was well established.

A 1950 census taker called their neighborhood the “negro quarters” and noted that there were “no street names”. Today, Railroad Avenue is called Annie Lee Keys Boulevard after Tan’s “adopted” daughter and in tribute to her community activism.

A quiet title action is a lawsuit in Florida that determines the true owner of a property. It's also known as a suit to "remove cloud on title".